How to Design Effective Shoreline Access

Shoreline access is important to all those who visit, play or work on shorelines. Well-managed access also protects the environmental values of shorelines.

For many communities, shorelines provide vital spaces for harvesting traditional foods like clams and oysters – and access to these resources impacts the ability for First Nations to carry out traditional harvests and management. Additionally, the beauty and openness of these areas contribute to overall health and well-being (Five Surprising Benefits of Nature-based Shorelines).

Shorelines are generally considered accessible to all citizens in Canada as they fall within “Crown” jurisdiction. Under the Nature-based Shoreline Project Checklist process available through the Province of BC, the restoration project design has to provide the following:

“Members of the public must be able to readily go around or cross over any constructed structures along the foreshore, i.e., access along the foreshore should not be impeded. Overall, the objective is to provide improved public access to the shoreline.”

The question of the importance of having free access to coastal shores is prominent across Canada. For example, in Nova Scotia, shoreline access is discussed in a Coastal Access Project podcast, ”Right of Way .” The podcast explores the issue of coastal access through the stories of property owners, communities, scientists, policymakers, environmental activists, surfers, and hikers.

Picture Credit: The Nova Scotian podcast "Right of Way" goes on a deep dive exploration of coastal access and jurisdictions limiting people's use of shorelines and the benefits they provide. Cover artwork by Laura Bonga.

Other programs, such as Shore Friendly in Washington State, require consideration of safe and reasonable access for all potential users (resource: Shoreline Master Programs Handbook: Chapter 9).

Considerations for Designing Effective Access

The Stewardship Centre for BC’s Green Shores® program provides guidance on nature-based solutions for shoreline properties. Among its many recommendations, shoreline access design is a key consideration, balancing ecological preservation with public and private needs. Homeowners and communities can refer to the Green Shores for Homes Credits and Ratings Guide (Credit 2.7, pages 93-95) for detailed insights. Owners and managers of public and commercial shoreline properties can refer to the Green Shores for Shoreline Development Guide for further guidance on shore-friendly access (Credit 2, pages 45-50).

A well-designed access route should protect the ecological integrity of riparian zones – the transitional areas in between the upland areas and the adjacent lake, river, stream or ocean. Shoreline access should also be designed to provide safe and reasonable entry while respecting homeowners’ privacy. Remember that unmanaged pet access can disturb wildlife, particularly nesting birds, pollinators and sensitive ecosystems.

Best practices for shoreline access include:

- Limit access paths to a minimal width and footprint and, if possible, avoid a linear design that runs straight to the shoreline.

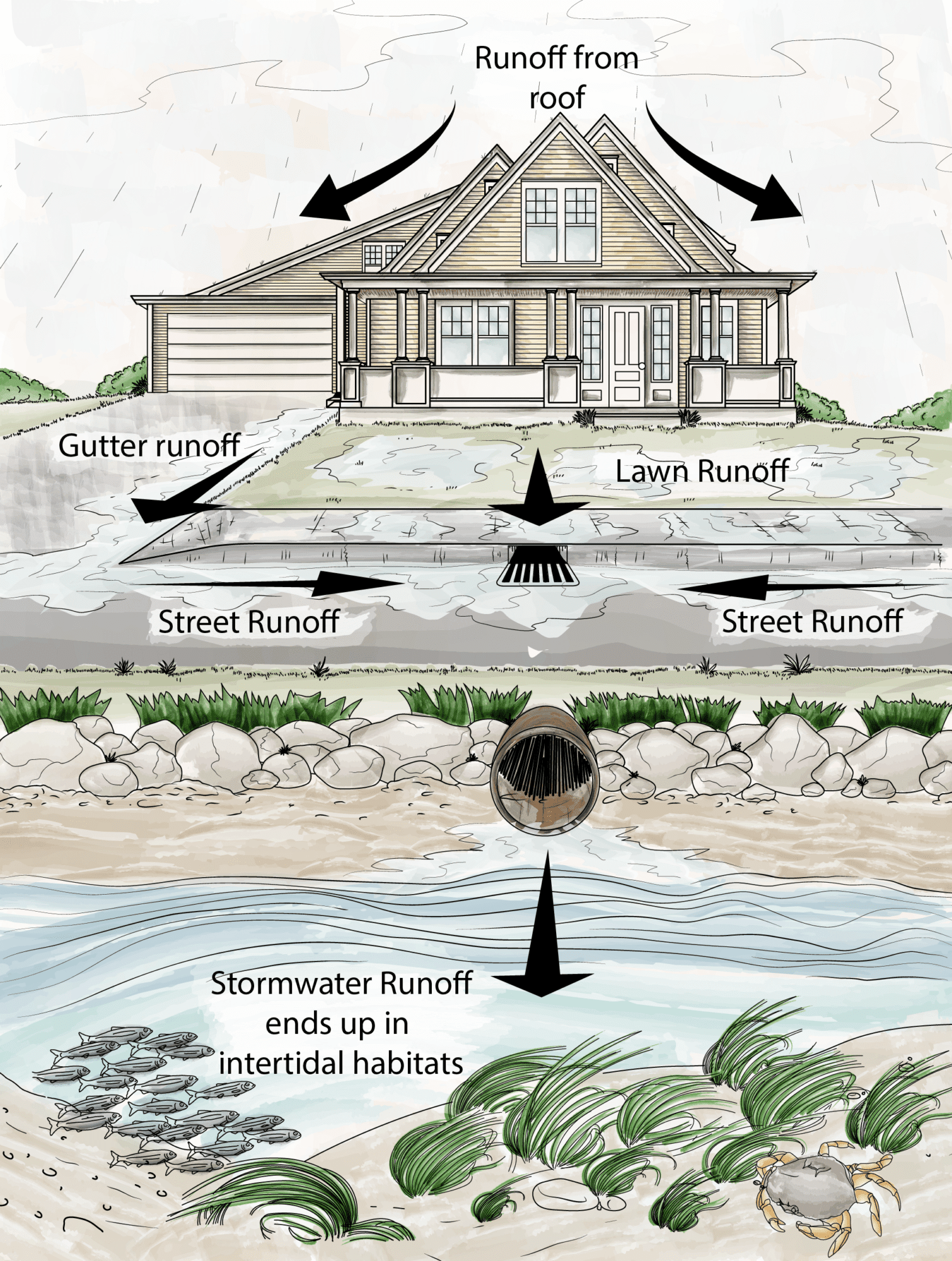

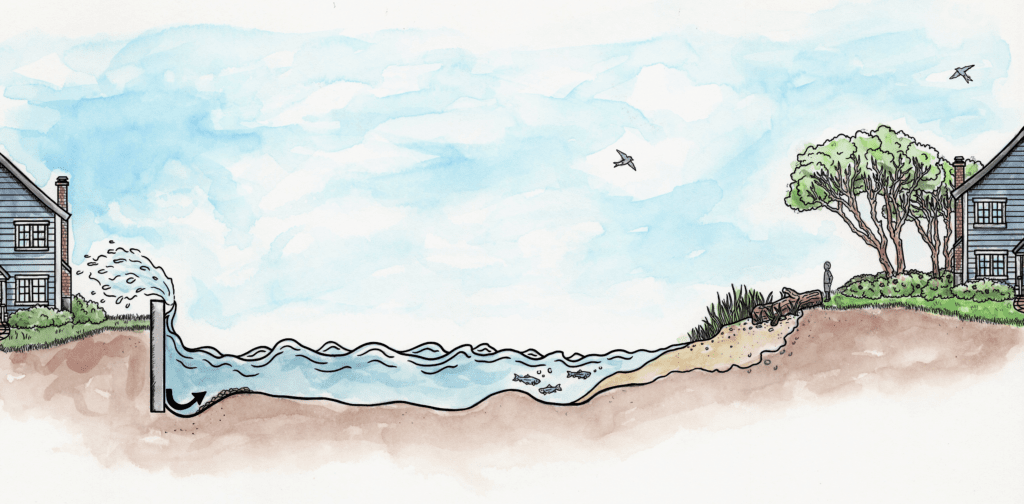

- Use permeable paths that allow water filtration and reduce overland runoff that may transport contaminants from the upland.

- Incorporate native plant buffers for habitat support and shoreline stability.

- Avoid artificial lighting on pathways, which can disrupt nocturnal wildlife.

- Ensure all required safety codes are adhered to for the access design.

- Provide designated entry points to minimize disturbance.

- Manage movement of pets on the shoreline through signage directed to owners, requesting that pets stay on leash. In many communities, there may be signage that restricts off-leash dog access to particular seasons or areas.

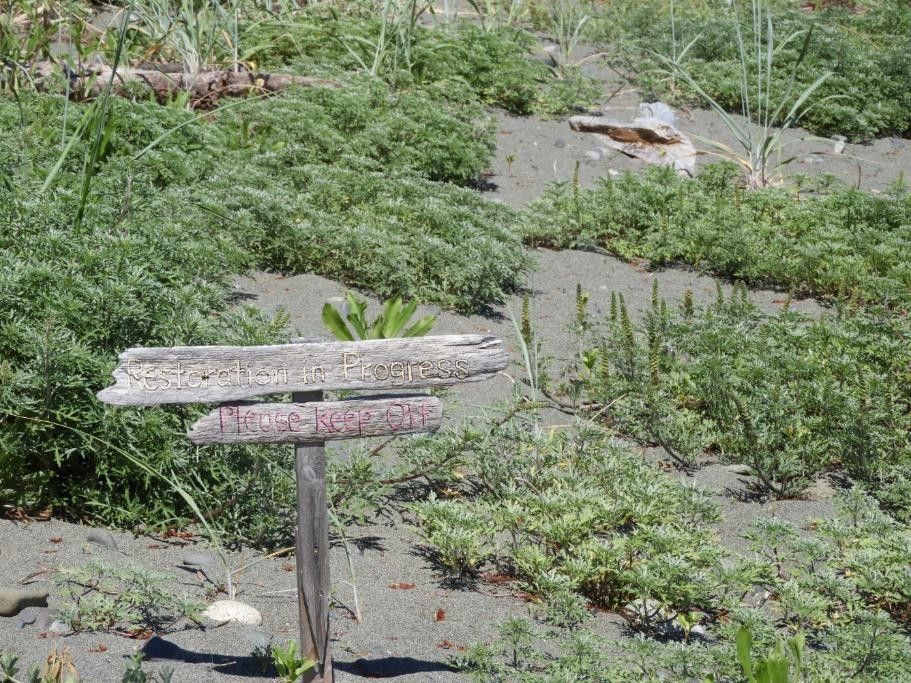

- Promote limited shoreline access in areas where wildlife values are key. Installation of temporary signage during active seasons for bird breeding (March –August), peak nesting (May-August) and fish spawning (October – December) to inform passersby about ecologically-sensitive times of the year. This should be based on local ecosystem information.

- Launch watercraft, such as kayaks, from designated areas to avoid damage to riparian vegetation. Since riparian ecosystems are sensitive to disturbance and take a long time to re-establish, it is best to launch boats from open shoreline areas (with sand/gravel) and preferably from the designated location to limit disturbance elsewhere.

- Public access doesn’t always mean direct shoreline entry. Alternative approaches include:

- Lookouts or breezeways for views.

- Interpretive signage highlighting historical, ecological, or cultural features.

How does habitat-friendly beach access support salmon?

- By keeping your beach pathway narrow, you are allowing more of your shoreline property to be vegetated with shrubs, trees and salt tolerant grasses, which means more food for salmon! Terrestrial insects will fall from the greenery into the water, providing a tasty snack for salmon passing by.

Photo by Fernando Lessa

- Pacific salmon, and many of creatures of the coastal food web, need clean water to explore in the nearshore environment. By opting for a beach path made of sand, gravel or other permeable materials, you are reducing the amount of runoff that enters waterways directly. Click here to learn more about how to manage stormwater runoff with nature-based solutions.

Example of shoreline access

See below for examples of Green Shores for Homes projects with good access design and features that demonstrate best practices. Visit the Stewardship Centre for BC's Green Shores for Homes Case Studies page for more examples.

A. Prospect Lake, Saanich

• The walkway includes a narrow, flat-rock path interspersed with native grasses, which connects to an untreated wood dock. The dock has spaces between the boards that allow natural light penetration to benefit aquatic plants and organisms below.

• Extensive riparian vegetation, including overhanging shrubs and trees, was retained for shade, temperature regulation, and habitat diversity.

B. Portage Road, Saanich

• The pathway was created with minimal width through the native riparian vegetation, to protect habitat and biodiversity. The walkway is surfaced with natural materials, and there is no artificial lighting.

• Shrubs and trees were retained to enhance habitat and stabilize the shoreline.

• The entire riparian area is protected under a legally established conservation covenant.

C. Agate Lane, Saanich

- The pathway is non-linear and made of untreated wood materials;

- Riparian vegetation was infilled with native plants and is protected from foot traffic both to and from the shoreline;

- No artificial lighting was installed along the path.

D. Songhees Walkway Pocket Beach Green Shores for Shoreline Development project: Victoria

- The public pathway is made of solid and yet permeable material, allowing for water infiltration and stability for wheeled carts, walkers and strollers to access the shoreline. This was important for the cultural use of this shoreline by the Songhees Nation with their traditional canoes.

- There is no artificial lighting, and the pathway integrates well with the natural shoreline edge.

E. Nile Road, Qualicum Bay

| Minimal vegetation diversity; Linear shoreline allows high water migration inland, particularly during storm events; | Non-linear pathway infilled with native vegetation; Path is made of permeable material, allowing water infiltration and decreasing overland runoff; |

Conclusion

Shorelines are special places that people and wildlife use and enjoy. By integrating these thoughtful design principles, we can ensure shoreline access benefits people while preserving the ecological and cultural richness of marine and lake shores. For more details, explore Green Shores and the Resilient Coasts for Salmon Nature-based Solutions for Climate Change - Resilient Coasts for Salmon project website to discover how sustainable shoreline management can work for you!

Cover image from SCBC's Green Shores for Homes project Agate Lane in Saanich, BC. Photo Credit Kelly Loch.

All photographs in the 'Examples of Shoreline Access' section by Kelly Loch, Stewardship Centre for British Columbia.