In nature, trees and soil help absorb water slowly. This helps break down pollutants and refill groundwater, which keeps waterways and our shorelines healthy. Stormwater management is the effort to manage runoff of rainwater or melted snow on streets, lawns, and other sites and the contaminants carried along with it.

Uncontrolled stormwater can negatively impact our lives and the environment in many different ways. It can contribute to flooding, which can damage infrastructure and endanger human lives. Stormwater runoff can also contribute to issues of erosion, leading to widening of streambanks, and failure of slopes. Stormwater washes contaminants and sediments into aquatic environments, degrading them. And, as the name implies, runoff moves over surfaces and does not infiltrate the soil, therefore it does not contribute to refilling groundwater. Groundwater is important as a source of potable water and for its contribution of cool, clean water to the base flows of streams during the warm dry season.

Managing stormwater can reduce flooding and property damage and improve the quality of water entering aquatic environments, including streams, rivers, and shorelines. Water absorbed on-site, through permeable surfaces such as a garden, special pavers or natural areas, helps to maintain groundwater stores and soil moisture, benefiting vegetation, including flower and vegetable gardens. You may even harvest excess rainwater in a tank to use at times of the year when water is in shorter supply.

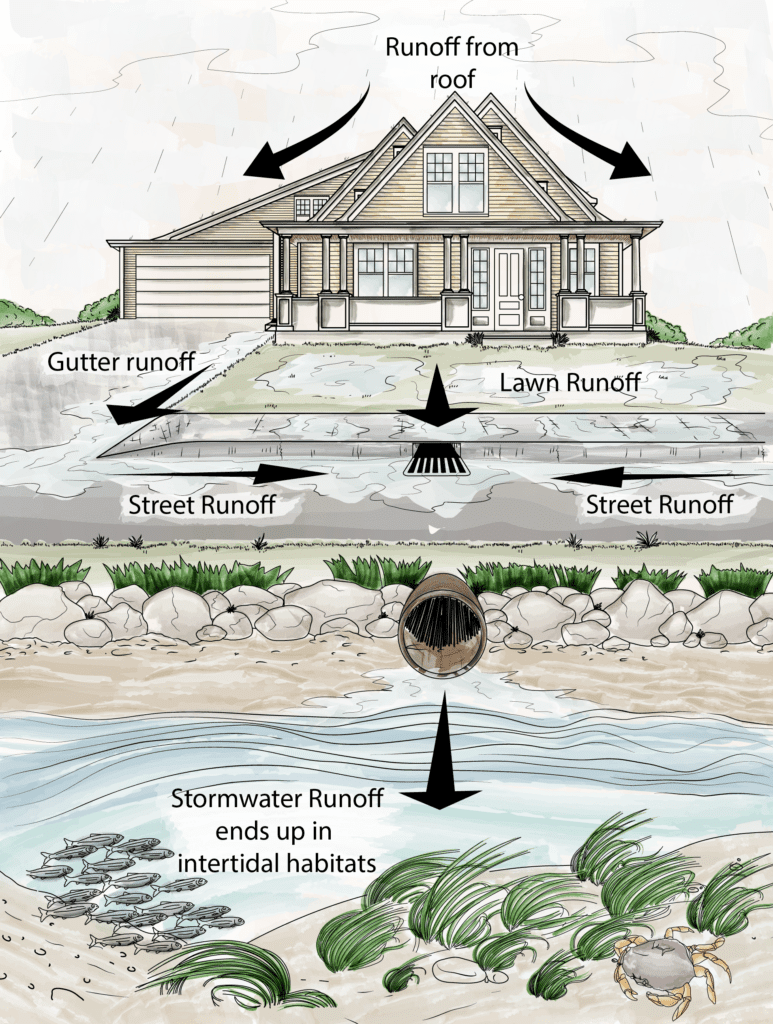

Impervious surfaces are hardened areas where rainwater cannot infiltrate into the ground. They can be made up of materials like metal, concrete and asphalt. Rainwater falling on impervious surfaces flows to stormwater drains that are often directly connected to streams, rivers, or the nearshore environment. During a storm, water that flows off impermeable surfaces may move very quick, much faster than it would naturally, and that can lead to erosion, flooding or ponding. Stormwater runoff can be a problem in towns and cities, since there are lots of impervious areas in the form of roofs, paved areas, and roads.

The illustration shows the movement of water runoff to the shoreline via paved surfaces and storm drains, which typically connect directly with waterways or the ocean. Illustration by Ravi Maharaj and Holly Sullivan.

As stormwater flows over impermeable surfaces, it collects debris and pollutants. Many of these contaminants have major impacts on our coastal ecosystems and human health. Let’s take a closer look at some common contaminants!

Road and Surface Contaminants

Oil and residues that can be found on driveways, streets and highways can be extremely harmful to aquatic environments. One example of a particularly concerning contaminant that moves into aquatic systems from roads is the compound used as an antioxidant to reduce tire wear, 6PPD-quinone. This compound flows from roadways, through surface runoff, into water courses. It is extremely toxic to fish and is lethal to coho salmon. Learn more about this nefarious contaminant from the Nature Conservancy, and click here to access a PSF brochure about 6PPD.

Excess Nutrients

Did you know that nitrogen and phosphorus are often found in large concentrations in runoff?

Nutrients such as these often originate from chemical fertilizers and animal waste (manure) that is applied to agricultural lands or gardens. While animal manure and compost are often a part of a healthy closed cycle agricultural operation, in large scale commercial operations, manure and chemical fertilizers are often applied in excess. During rain events, the nutrients that are not bound in the soil or plant parts will be washed away over the soil surface.

When excess nutrients enter our waterways, they can feed the phytoplankton and algae that live in those waters. While this may sound like a positive effect, the sheer amount of those nutrients can trigger larger areas of algae to bloom all at once. When these algae complete their life cycle and die, they decompose into the water column, a process which consumes oxygen. This can leave our waters de-oxygenated and inhospitable to aquatic life, or eutrophic. You can do your part on your property by planting native plant species that require little to no inputs of nutrients to grow and thrive. You can learn more about nutrient runoff issues and how land managers can help to reduce their contribution of nutrient pollution in this article from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Garbage

During major rainfall events, the flow of stormwater across impervious surfaces can be strong – it can even be strong enough to pick up litter like plastics bags, bottles and single use cups and carry those debris out to nearby waterways. Over time, this litter breaks down into smaller and smaller particles, but the plastics in these materials remain in the environment as microparticles, which are still detrimental to aquatic life. Plastics consumed by wildlife disrupt feeding and growth by physically filling their stomachs without providing nutrients. As their bodies attempt to break down these materials, it can result in bioaccumulation of toxins in their tissues.

Learn more about microplastics pollution and how to reduce your contribution through your laundry and clothing choices in this Tool Kit article.

Other common contaminants include suspended sediments, pet waste, herbicides, and pathogens that could be dangerous for human health. Learn more about the most common stormwater contaminants and their potential impacts in this page of the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency’s website.

We can embrace nature-based solutions to help manage the rate, amount, and direction of stormwater. Also referred to as Low Impact Development (LID), nature-based solutions allow rainwater to filter into the ground, reducing contaminants from runoff before entering receiving water bodies. Here are six techniques you can try out:

Increase permeable surfaces by installing permeable pavers, gravel, or grass that allow water to be absorbed on-site rather than concrete paving. By adding space between paving stones where the water can infiltrate the soil, we can reduce the total area of impermeable surfaces and the amount of runoff leaving our properties. Learn more about permeable paving stones through the Green Building Alliance.

Plant and maintain vegetation, such as trees and shrubs. The canopy of leaves and branches can protect soil surfaces from erosion by intercepting falling rain during intense storms, and the roots help to hold onto the soil. Remember that messy is beautiful and a diverse garden will have many benefits, including storm water management. If you are concerned about viewing opportunities from your property, native shrubs are a great option to retain soil cover while not obstructing views.

Wherever possible, choose native plants well adapted to the site. Native species will require little to no input of fertilizer or herbicides, resulting in a lower impact on nearby waterways.

Look out for plants that not only absorb water but clean it, too. Some sunflower species are phytoremediators, meaning they can remove heavy metals like zinc and copper from soils. Try out these other phytoremediators suggested in this Basmati article.

Support healthy soil and increase water absorption on your property by adding mulch such as grass clippings, wood chips, leaves, and other organic materials.

In addition to absorbing water, healthy soils help clean it, too – did you know that there are microbes in the soil that help with the bioremediation of contaminants? There are microbes that naturally are a part of the soil doing this work all the time, but bioremediation can be used on a large scale with powerful to help clean up things like oil spills.

Consider a green roof. Green roofs have a waterproof membrane, growing medium, and soils that support living plants and are designed so that the weight of the soil and plants is less than or equal to the weight the roof structure can safely support. According to the Stormwater Center, green roof can reduce annual runoff by 50 to 60%.

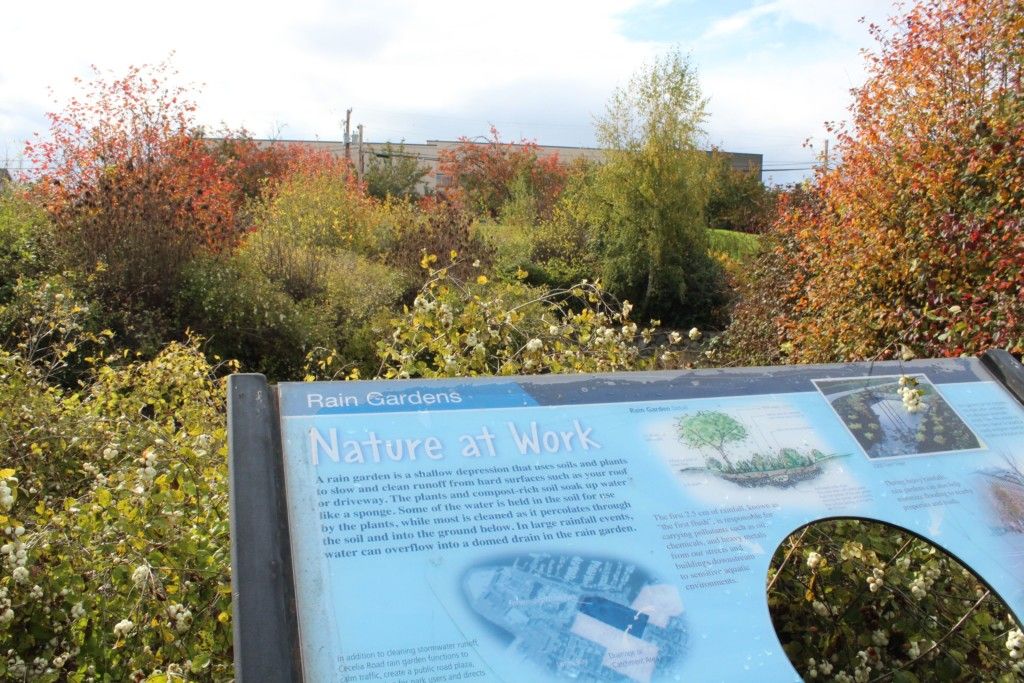

Install a rain garden or bioswale to retain and absorb water runoff from roofs. A rain garden is specially designed to treat stormwater runoff. It works by collecting water in a sunken garden space planted with native species, which allows the water to infiltrate through a constructed soil layer to the native soils below.

Reduce runoff from your roof by using a rainwater harvesting system. Stored rainwater can be used for garden irrigation, washing your car, and other uses around the home. More information on rainwater harvesting can be found within the Regional District of Nanaimo’s comprehensive guide for best practices and the Capital Regional District (CRD), which includes a list of suppliers for rainwater tanks and other tools to help create a rainwater harvesting system that will work for your property.

When considering what nature-based stormwater management techniques will work for you, take the time to understand how your property interacts with runoff. Notice where water runs over impermeable surfaces, where it originates, and where it goes. This knowledge can help guide what actions will be most beneficial on your property and where those actions should be applied.

For example, a riparian area or meadow filled native plants, such as camas lilies shown below, can provide a buffer between the upland and shoreline, slowing and treating water runoff before it enters a waterway.

Applied on a larger neighbourhood scale, the benefits of stormwater management can be significant. Check out these examples of green roofs, rain gardens, and other runoff management infrastructures that have been successful in Metro Vancouver, Victoria, and Seattle. Nature-based solutions can be used on all scales of projects, from your front garden to municipal park restoration! in any case, using Green Stormwater Infrastructure can help to capture and slow the flow of water, clean stormwater from pollutants, and store and convey stormwater to reduce flooding.

Check out these local stormwater management projects. On the left below, is a stormwater management project by BC transit (handyDART) and Salmon Safe at Craigflower Creek in Victoria. It includes nine rain gardens that help filter contaminants and a series of weirs and pools to help mitigate the flow of runoff from the nearby highway. This incredible project will help reduce the impacts of runoff into Craigflower Creek, an important waterway for Pacific Salmon, waterfowl, and amphibians. The project is built to process runoff from even a 200-year rain event! On the right is a recently installed local rain garden by Peninsula Streams and Shorelines (PSS) in partnership with school district 61 in Victoria. The rain garden basin will help collect runoff from the school’s paved surfaces; native plants will soak up water, filtering out the contaminants that might otherwise flow into waterways.

It is important to remember that application at the homeowner scale matters. Using some or all of the above techniques supports homeowners and the environment in managing stormwater. Using the Green Shores for Homes guide also can help, learn more about Green Shores in this article. With Green Shores for Homes, you get credit for reducing impermeable areas, retaining rainwater for household and landscape use, and for maximizing areas of vegetation and absorbent landscapes. By working with a qualified professional and using Green Shores for Homes and local stormwater design guidelines, a system can be developed to protect properties from the extreme precipitation events expected with climate change. With stormwater, every drop counts!

The CRD website has a number of helpful pages for managing stormwater, such as this page about preventing stormwater pollution.

Vancouver has a 'Rain City Strategy' which depicts many stormwater solutions in this appendix of green rainwater infrastructure.

Learn more about ground water recharge in this article by Andreas Hartmann.

Get support for stormwater management from Green Shores.

Stormwater Management Planning, Guidelines of Best Practices.

Check out the Water Balance Express tool, which can help homeowners understand runoff patterns in the watershed and implement solutions targeted to meet local infiltration targets.

Photo credits: Luke Southern on Unsplash; Nicole Christiansen; Liz Harrell on Unsplash; Yogendra Singh on Pexels; Maria Catanzaro; Lehna Malmkvist; Kelly Loch.