Explore the examples below to see how cities are considering nature in their coastal infrastructure.

The City of Seattle is a great example. When repairs were needed for the downtown waterfront area, the city took this opportunity to try out some innovative solutions and rebuild the area with migrating Pacific salmon in mind. The newly designed pier and seawall beneath it are part of a larger project at Seattle’s Waterfront Park. This project aims to create open space for engaging and educational events, plus coastal habitat that supports marine life in the urban location.

Rather than seawalls that plunge into deep water and are covered by solid walkways and structures, which create dark areas lacking habitat complexity, food resources and refugia that young salmon need (learn about these in this post about coastal modification impacts on salmon), the restored areas have a number of modifications so as to retain shallow and complex intertidal zones that receive sunlight.

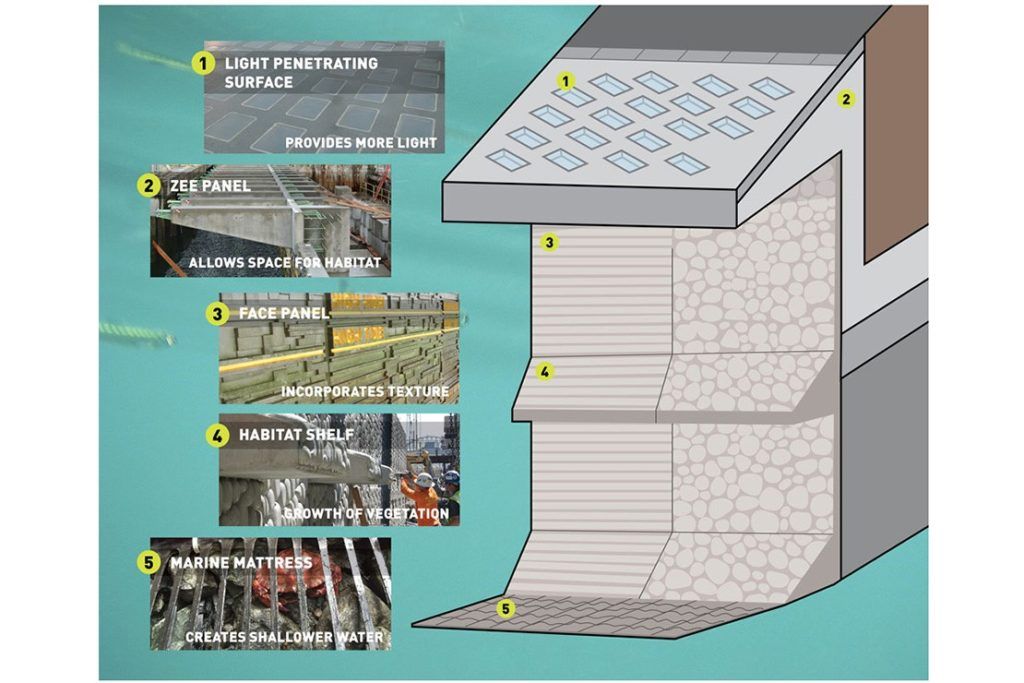

The schematic below, from Waterfront Seattle, shows how the seawalls under the walkways and piers have been rebuilt.

Starting at the top, walkways were outfitted with light penetrating surfaces (1,2), including grating and glass blocks, to light up the areas below.

Instead of a flat featureless seawall, textured panels and habitat shelves were added to increase surface complexity (3,4). The texture promotes settlement of algae and invertebrates that, in turn, attract small fish. In the build, they have experimented with different types of texture, emulating cobbles in some areas and striated rocks in others.

Towards the low tide mark, so called ‘marine mattresses’, were installed (5). These added structures create shallow habitat that provide small critters and young salmon refuge from larger predators.

Researchers from the University of Washington’s Wetland Ecosystem Team, who provided input, are monitoring the project’s success. They are seeing that the steps taken are increasing biodiversity and improving habitat value. As hoped, salmon are using these areas more than they were under the traditional structures (see article).

Above it all, in the popular public area, signs about the work provide an excellent learning opportunity for visitors to engage with. A number of articles published in news sites also helps create a buzz of interest in the work to a wider audience (see Hakai Magazine and NPR podcast).

See the students in UW School of Aquatic and Fisheries Sciences present in this work in a seminar hosted by Sound Water Stewards.

Seattle is not alone, a number of other cities around the world are rethinking their water fonts. The World Harbour Project, headquartered in Sydney, Australia, has engaged a number of major international harbours, including four in North America, with the primary aim to promote research and restoration of ecosystem function in highly urbanized areas.

Examples of initiatives include:

Vancouver is reconsidering its waterfront areas as well. The recent storms that battered Vancouver – causing flooding and erosion – served as a shocking preview of what is to come with sea level rise. It is clear that innovative planning will be needed. Will nature be included in the new designs? Learn about the Sea2City Design Challenge, which aims to establish a plan for urban development and ecological revitalization for the False Creek floodplain of downtown Vancouver.

The only oyster species native to BC, the Olympia oyster, is struggling across its range due to historical exploitation and a number of stressors that prevent them from recovering. As a result of this, the Olympia oyster has been listed as a species of special concern. As important ecosystem engineers, meaning they perform important functions for the environment like building habitat (reefs), supporting biodiversity and improving water quality, encouraging oyster recovery should be a priority.

When the Craigflower Bridge, in the Gorge Waterway of Victoria, was being rebuilt the native oysters were looked after. The Olympia oysters around the old bridge were salvaged – collected and moved to artificial reefs – so as not to lose the creatures during the deconstruction. On the new bridge, textured panels were added to the footings and oyster reefballs, which are made up of substrate that encourages oyster settlement, were also placed around the Gorge Waterway to encourage more Olympia oysters to establish. Coastal Collaborative Sciences, who is carrying out the program, hopes to relocate the oyster reef balls to other locations in hopes of re-establishing populations elsewhere.

Photo, provided by World Fisheries Trust, showing dense oysters colonized on a reefball in the Gorge Waterway.