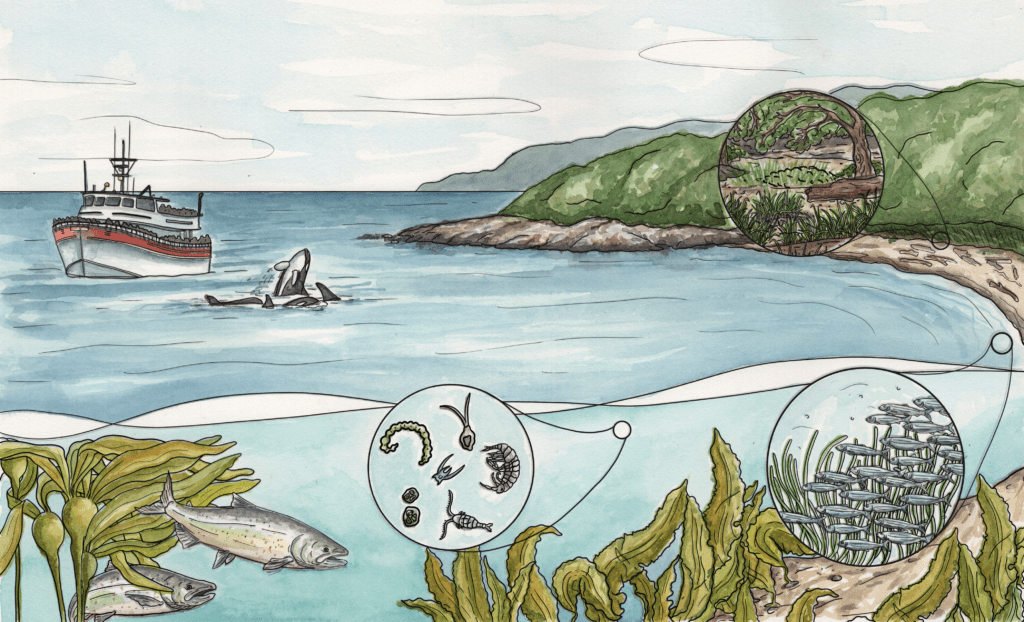

Coastal and estuarine areas, which are often extensively modified in urban centres with shoreline hardening and structures such as docks and piers, are vital stop-over habitats where young salmon grow, adjust and prepare for their life at sea. Features such as seawalls, riprap, docks, and piers, alter how shorelines function and they also affect Pacific salmon during their coastal phase of life. How well salmon grow during their time in coastal areas is directly linked to their success out at sea, and ultimately, whether they make it back to spawn the next generation.

When Pacific salmon first migrate down to coastal habitats, they preferentially use shallow areas and shift along the depth gradient and between habitats as they grow. Shoreline modifications, like seawalls that extend into the lower subtidal zone, eliminate shallow areas and complex habitat gradients. Shallow habitats are particularly important for the smallest salmon as they offer refuge from larger predators that cannot access those areas. Without the shallow areas, young salmon must occupy the same areas as larger fish, leaving them more vulnerable to predation.

On armoured shorelines, salmon are unable to access their preferred prey items. Studies have found that shoreline armouring reduced the number and diversity of epibenthic invertebrate (critters that reside on or above the rock, sand and mud of the seafloor) and the availability of terrestrial insects compared to unarmoured areas. As a result, when young salmon are next to a seawall and other artificial structures, they end up feeding on alternative prey types such as planktonic prey that might be harder to catch and less nutritious.

Quality shallow habitat is also lost under traditional overwater structures, such as piers and docks. The areas beneath them are bleak. The structures cast too much shade so seagrasses and algae can not thrive below. While you may be able to spot crabs and some barnacles or mussels under these structures, overall, there are few fish or other animals. Salmon also avoid these areas – it is too dark – and the lack of light seems to make salmon nervous. They also cannot see their predators, find ample prey, properly orient themselves, or school together. They end up altering their natural behaviours and avoid the shallow areas that should be their safe havens with plentiful food. Instead, salmon end up swimming in deeper water and expending more energy.

Coastal modification also disrupts overall land and sea connectivity. Coastal riparian vegetation is lost on modified shores along with the insects that would fall into the water – and these terrestrial insects are another important food source for salmon. Surf smelt, a prized prey item for salmon as they grow in coastal areas, also suffer without overhanging coastal vegetation. The shade of the vegetation regulates the temperature of the upper shoreline and this is important for successful surf smelt beach spawning.

Watch this video by expert Dr. Stuart Munch from NOAA to learn more about the impacts of shoreline modifications on salmon and solutions to mitigate them in Puget Sound. Video provided courtesy of Raincoast Conservation Foundation.

Credits: Illustration by: Holly Sullivan; Salmon in city photo by Tavish Campbell on Flickr