Green Shores® is a science-based program of the non-profit Stewardship Centre for BC that focuses on positive steps to reduce the impact of development on shoreline ecosystems and helps waterfront property owners restore natural shorelines and enjoy the many benefits they bring. Learn more about it in this post.

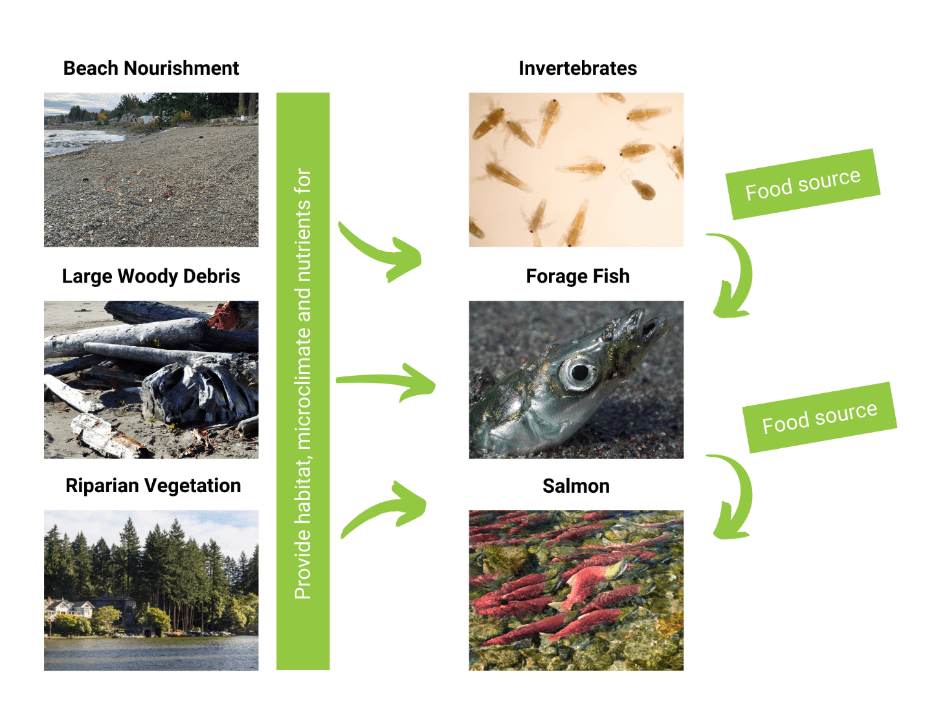

Rather than hard armour for shoreline protection - which can have detrimental impacts on salmon, properly designed Green Shores projects work with natural conditions and offer a suite of more desirable environmental outcomes. For instance, soft shore designs encouraged by Green Shores guidelines provide habitat for invertebrates which are the food sources for salmon, other fish species, birds, and marine mammals. In addition, beach nourishment with sediment may provide spawning or breeding habitat for forage fish species (e.g., Pacific sand lance, surf smelt) that are key sources of food for salmon.

Green Shores projects use beach nourishment, large woody debris and boulders, and native vegetation to improve shoreline function and resiliency and provide habitat, microclimate and organic nutrients to support habitat for invertebrates, forage fish and salmon.

Now, let's take a look at two examples of Green Shores projects and how they support salmon.

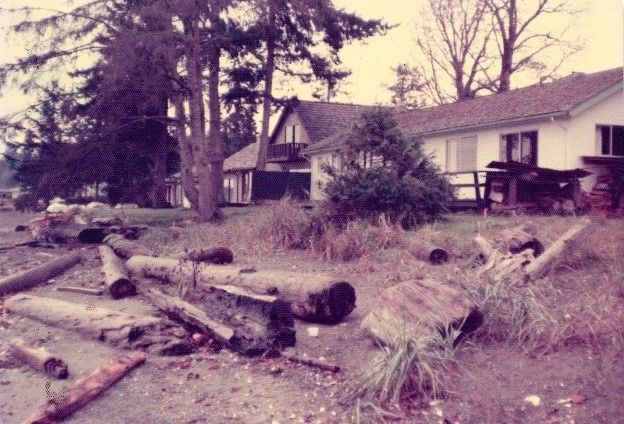

Before Restoration

The site for this Green Shores for Homes project is located in the Parksville-Qualicum Wildlife Management Area, which protects over one thousand hectares of habitat supporting Pacific salmon and trout species (SNC Lavalin Inc, 2015). Historically, the entire Qualicum Beach waterfront had a gentle grade to the foreshore and a sandy beach suitable for forage fish spawning activities.

Over time, this shoreline was significantly altered by man-made structures, including concrete bulkheads, seawalls and rip-rap. These structures have limited the local supply of fresh sediment and reflected energy in the upper bench during storms, leading to the loss of critical habitat for forage fish. Waves were overtopping, properties were flooding, and the upper beaches were eroding.

The photo on the left was taken before the Green Shores for Homes restoration took place. Note the change of beach substrate to gravel and cobble, showing a loss of sediment compared to a historic photo of the site (above). In addition, the beach grade now “drops off,” making access to the shore more difficult, limiting shoreline vegetation establishment and reducing the habitat quality for forage fish.

Photo credit: Kelly Loch

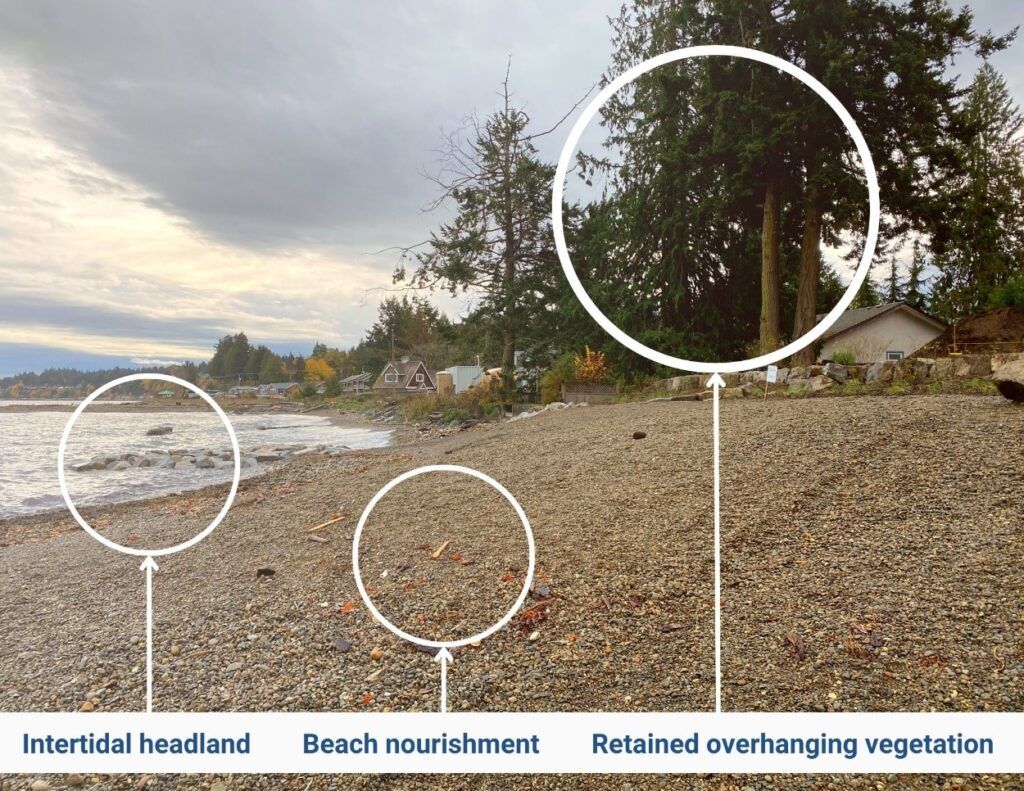

Many nearshore fish and wildlife species need functioning high intertidal habitats as a source of food, migration corridors, cover, micro-climate effects, and spawning habitat. To improve natural processes and nearshore habitat conditions, it was most beneficial to remove existing hard armour from an armoured waterfront property and apply a nature-based Green Shores design. In 2020, the homeowners began a restoration project to address the negative impacts of pre-existing hard armour

The Green Shores for Homes Restoration

As part of the restoration design process, it was noted that the estuary of the Little Qualicum River, located within the 2 kilometres of the property, supports a number of salmonid species, including chum, coho, Chinook, pink and sockeye salmon, kokanee, brown, bull, rainbow, steelhead cutthroat trout, and Dolly Varden trout, as well as bass, sunfish, lamprey, and threespine stickleback.

In addition, out-migrating salmonid smolts use nearshore habitats such as that fronting the subject site. Hence the restoration work needed to help improve and enhance the habitat for forage fish and salmonids and address concerns like rising sea levels and coastal erosion at the site.

Based on consultation with shoreline professionals and to meet Green Shores for Home certification and application requirements, the following were key parts of the restoration design:

The Green Shores for Homes design has increased protection of the infrastructure and created a healthy, resilient shoreline environment that is free of contaminants but full of organic input and substrate for forage fish, salmon and other wildlife.

The project from the perspective of a homeowner:

“We worried about our waterfront property whenever a storm was forecast because our concrete and rock seawall, which had been installed before we bought the property, was failing. The beach in front of it had significantly eroded and our experience has been that more frequent and stronger storms are often overtopping it… The new design has much better protection from storms. The November 2021 and January 2022 storms that hit the west coast were so intense that they destroyed well established seawalls in Stanley Park. These storms also destroyed seawalls and caused coastal flooding in our community on Vancouver Island but our property fared extremely well and the waves didn’t even reach my property line.

Best of all, extensive habitat has been created and we see new life all the time. Beach grasses are starting to grow, sea life is returning, and sandy tidal pools are starting to form.”

– Qualicum Beach GSH homeowner, 2022

Before Restoration

The New Brighton Park Shoreline Restoration Project transformed what was formerly part of an industrial harbour into a restored coastal lagoon and marsh system. The project intended to address the high mortality of juvenile fish migrating through Burrard Inlet by creating shoreline habitat and restoring tidal influence to support juvenile Chinook and chum salmon rearing.

The project site is located along the south side of Burrard Inlet immediately west of the Second Narrows Bridge in Vancouver, B.C. This site and nearby coastal areas have been used by Indigenous Peoples for millennia.

In the 1930s, the park was established in an industrial harbour. Thirty years later, in the 1960s, extensive filling of the intertidal zone occurred in the north portion of the park, shifting the shoreline by 150 metres and reducing intertidal, backshore and marine riparian areas. These changes negatively impacted native vegetation and shoreline habitat, leading to high mortality of juvenile Chinook and chum salmon migrating through Burrard Inlet.

New Brighton Restoration Project before GSSD. Photo from Green Shores for Shoreline Development Ratings and Credits Guide.

The Green Shores for Shoreline Development Restoration

Because of its location within a high-use urban environment, extensive consultation was completed before development, including public consultation and collaboration with the šxʷməθkʷəy̓əmaɁɬ (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh-ulh (Squamish), and səl̓ilwətaɁɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) First Nations. Based on this consultation process and to meet Green Shores for Shoreline Development certification and Prerequisites, the following were key parts of the restoration design:

The Green Shores for Shoreline Development design in Brighton Beach Park created upper, mid and subtidal salt marsh areas and enhanced instream and riparian habitat for salmon species feeding along the shoreline of Burrard Inlet. The project also helped restore tidal influence, connected Hastings Creek and the newly created saltwater marsh areas, acting as estuaries for juvenile salmon, and protected sediment essential for salmon spawning. Creation of additional intertidal and riparian habitat with an additional 290 m of shore length increased the overall ecological function of a critical area for juvenile salmon (chum and Chinook) and for resting and feeding shorebirds.

“We are thrilled that we have been honoured—along with our partners—with this environmental stewardship recognition. The restoration of this beautiful place as an oasis of biodiversity in the urban environment is one of this board’s proudest achievements.”

- Vancouver Park Board chair, Stuart Mackinnon, 2018

Juvenile salmon using the wetland during the second spring season after connection to Burrard Inlet (May 2018).

Interested in getting help, guidance and certification with Green Shores for Homes or Green Shores for Shoreline Development project? Learn about the process in this Tool Kit article and discover more about nature-based solutions for shorelines here.

Stewardship Centre for BC (2015). Green Shores for Homes: Credits and Ratings Guide. 138 p.

Stewardship Centre for BC (2020). Green Shores for Shoreline Development: Credits and Ratings Guide. 114 p. Link (direct download, 4.4 MB).

Northwest Hydraulic Consultants Ltd. (2021). Concept designs for neighbourhood-scale coastal adaptation measures in Royston and Qualicum Beach, BC: Final Report. 51 p.

Bridges, T. S., J. K. King, J. D. Simm, M. W. Beck, G. Collins, Q. Lodder, and R. K. Mohan, eds. 2021. International Guidelines on Natural and Nature-Based Features for Flood Risk Management. Vicksburg, MS: U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center.

Sobocinski, Cordell, J. R., & Simenstad, C. A. (2010). Effects of Shoreline Modifications on Supratidal Macroinvertebrate Fauna on Puget Sound, Washington Beaches. Estuaries and Coasts, 33(3), 699–711.

Toft, Dethier, M. N., Howe, E. R., Buckner, E. V., & Cordell, J. R. (2021). Effectiveness of living shorelines in the Salish Sea. Ecological Engineering, 167, 106255.