Coastlines are naturally dynamic systems and this can be a good thing for adapting to climate change if we understand and respect the natural processes at play. By working with nature, we can increase our resiliency to the impacts of climate change while also supporting and protecting biodiversity and human well-being.

Opting for more natural solutions for shoreline protection rather than seawalls, creates a more resilient habitat that can support juvenile salmon as well as forage fish and invertebrates that salmon feed upon.

Here, we share a number of considerations and nature-based strategies for protecting our shorelines and communities.

Protecting healthy and functioning coastal ecosystems starts with attention to the areas above the high tide mark, or the ‘upland’. By managing what happens on the upland, shorelines can be protected from excessive run‑off, contaminants, and erosion that would otherwise contribute to shoreline degradation. Here are a few suggestions:

Retain trees and snags – Avoid clearing of trees and shrubs along the shoreline as these provide important functions, for example as a food source, for shading, and riparian zone stabilization.

Practice eco-friendly gardening – Remove invasive species and encourage native species, and avoid chemical pesticides and fertilizers.

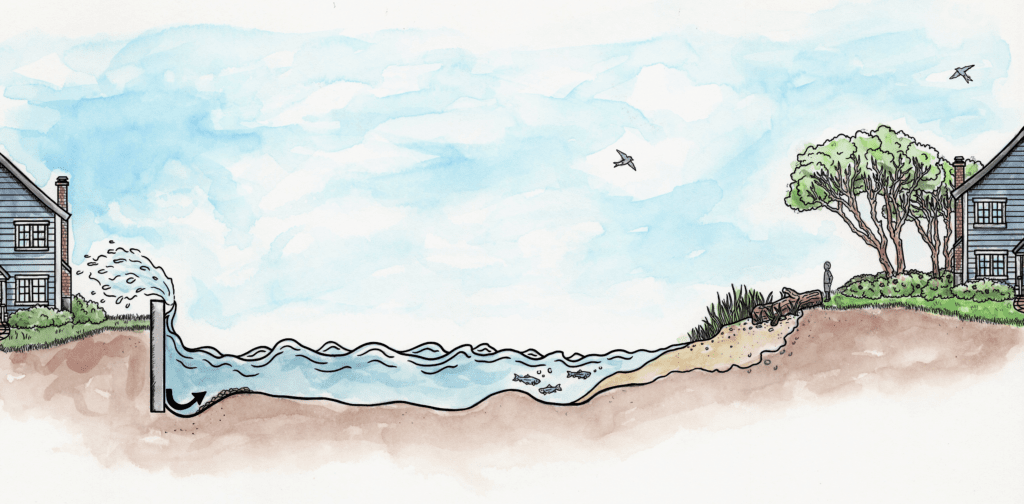

Reduce and treat run‑off – Use strategies such as rain gardens, permeable pavers and rainwater capture systems to minimize run-off from your property which can help reduce surface erosion and prevent contaminants from flowing into the aquatic environment.

Protect the riparian zone – A healthy riparian zone is key to the health of the shoreline as it acts as a buffer between the upland and the foreshore. The first step it to protect what is there: but if the backshore vegetation has been cleared in the past, try to replant it with native species. Below is a table of suitable species for our local coastal riparian zones you can source from a native plant nursery.

| Trees | Shrubs | Grass & Wild Flowers |

| Arbutus | Nootka rose | beach wild-rye grass |

| Douglas-fir | oceanspray | red fescue |

| Sitka spruce | red flowering currant | entire-leaved gumweed |

| shore pine | snowberry | large-leaved lupine |

| red alder | mock-orange | seashore lupine |

| big-leaf maple | sweet gale | beach pea |

| Pacific willow | salal | silvery burweed |

| cascara | Oregon-grape | beach strawberry |

| Hooker's willow | thimbleberry | sea-watch |

| Douglas maple | salmonberry | cow-parsnip |

| Scouler's willow | Indian-plum | Cooley's hedge-nettle |

| Pacific crab apple | black twinberry | common yarrow |

| vine maple | kinnickinnick | wooly sunflower |

| western red cedar | Pacific ninebark |

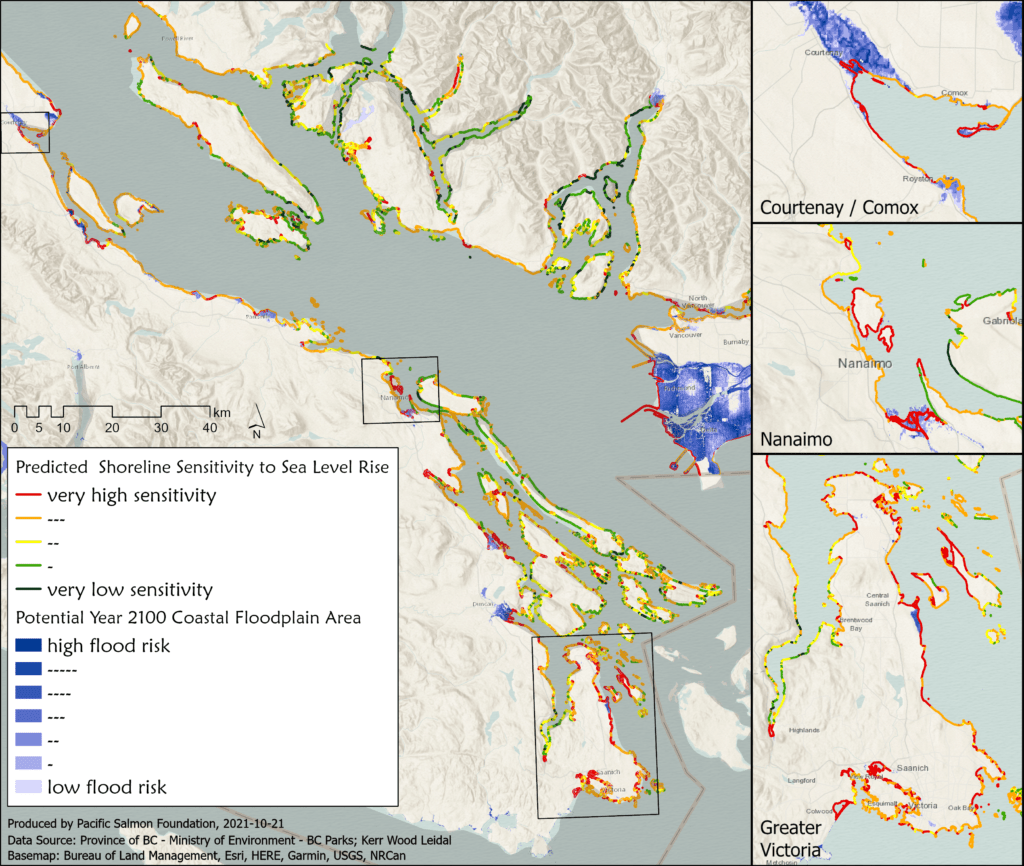

Sea levels are rising – how a given area will be impacted will depend on the region and a number of other factors such as erosion and deposition rates, and geological factors like uplift and plate tectonics. In British Columbia, sea level rise is projected to be greatest on the north coast, the Fraser Lowland and southern Vancouver Island. See this map which shows vulnerability to sea level rise and coastal flooding.

Sea level rise will increase tide levels and how far seawater reaches onto land, influence the duration and frequency of inundation, exacerbate coastal erosion, and even cause the loss of nearshore habitat. Coastal modifications can exacerbate these impacts. To adapt we will need to:

Avoid further development directly on shorelines – Protect and preserve the natural areas we still have. Preserving shorelines in their natural state helps ensure important habitats are available to support biodiverse ecosystems and our coastal food web.

Accommodate for sea level rise – Increase setbacks, move infrastructure back if possible, and build any new structures further back from the shore. There is often a required regulatory setback that is established by local government regulations and this may vary by area. A safe setback distance that accounts for local sea level rise should be calculated based on site conditions by a qualified professional, whom would also ensure regulatory conditions are met.

Remove existing seawalls, riprap or other modifications to the shoreline – These structures, which are built with the intention to protect coastal infrastructure, actually disrupt coastal processes and are not an effective long-term solution for adapting to sea level rise. A shoreline is most resilient when it can function as an intact ecosystem.

Successful restoration that improves ecosystem function and protects shoreline infrastructure requires a complete understanding of the dynamics of the area of shoreline you are working on. Enlisting qualified professionals (coastal geomorphologists/engineers, landscape architects, environmental consultants and biologists) is a critical step and will help you confidently design and plan a solution that considers natural coastal processes, shoreline erosion risk, and the dynamics of the ecosystem as a whole. The Stewardship Centre for BC has compiled a list of Green Shores Approved Professionals that have the skills and experience for such projects.

Depending on the site being restored some nature-based solutions that may be recommended include:

Recontour the beach profile – Recontouring can create great habitat benefits and provide shoreline protection. The aim of recontouring is to alter the slope of a beach so that it has a gentle gradient that will naturally dissipate wave energy. The process involves large machinery removing sediment from some areas and adding it to others to create the desired effect. Depending on the dynamics of a site, it may require maintenance over time to preserve the slope profile.

Beach nourishment – Sediment that is lost through erosion and not replenished by natural coastal processes can be replaced through a process called beach nourishment. Coastal modifications, such as groynes, jetties and breakwaters, disrupt longshore drift, which is responsible for maintaining the sand on beaches. Without natural replenishment, beaches that were once sandy or gravelly, may be stripped to cobble stones or bedrock. Having the right types of sediments on beaches is vital for forage fish, which spawn along the high tide line. To ensure the best habitat outcome, consult with a shoreline professional with expertise in coastal processes and forage fish requirements. They may suggest a ‘forage fish’ sediment mix that is specially formulated to suit the needs of species like Pacific sand lance, Pacific herring and surf smelt.

Incorporate large woody debris – Drift wood logs and other large woody debris can be placed along upper beaches and backshore, typically beyond the reach of the waves, to stabilize the shoreline and provide micro‑habitat for vegetation and animals. Depending on where they are placed, the natural untreated logs that are brought in may need to be anchored, either by partial burial or placing between rocks, to ensure they will not float away on the next high tide. Ideally, the logs will include intact roots or branches and be Douglas fir or western red cedar as they are naturally rot resistant. Once in place, the logs can help reduce erosion and accrete additional sediment on which dune grass and other shoreline plants may establish, further stabilizing and building up the beach.

Stabilize the shoreline with vegetation – Planting the riparian zone will stabilize sediment and prevent erosion along the shoreline. Having intact vegetation along the shoreline will also increase biodiversity, support marine food web linkages, and create incredible wildlife viewing opportunities. Besides planting native plant seedlings, there is another common method of revegetation, known as live staking, which involves sustainably harvesting cuttings from specific native species near by (e.g. red alder, snowberry, and Scouler willow) and staking them into the sediment and for them to eventually re-grow and stabilize the bank.

Here is a photo from a marine riparian restoration on Thetis Island by SeaChange Marine Conservation Society, led by Dave Polster. Also see this video of a shoreline slope restoration near Victoria.

A great example where all of these methods were utilized is the Weaverling Spit Restoration Projects by Samish Nation and Coastal Geologic Services, in Samish Territory, Anacortes, Washington. The project involved multiple phases of restoration along the shoreline including a long-term plan for managed retreat on Tribal Lands to allow for landward habitat migration. Below you will see how the shoreline was re-graded and restored and the benefits that have been achieved.

Prior to the restoration (left) Fidalgo Bay Resort was vulnerable to storm surges and experienced flooding and infrastructure damage. After regrading the shoreline and supplementing sediment (right), the site is more protected.

Weaverling Spit was experiencing erosion and, with lawn extending to the shoreline, there was no habitat connectivity (left) prior to recontouring the beach and planting riparian vegetation (right). The site is now more resilient to storm events and provides valuable habitat again. Large woody debris has naturally recruited and brought with it additional habitat and shoreline stabilization benefits described above. The beach was nourished with a forage fish sediment mix and, incredibly, they found surf smelt spawning the very next day!

Check out these helpful resources for additional information:

Put together for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and adapted by the Stewardship Centre for British Columbia, Your Marine Waterfront Canadian Edition provides ways to promote healthy shorelines while protecting waterfront properties. Included are guidelines for site assessments and design techniques to plan and restore your shoreline and other helpful resources for shoreline property owners.

The Washington State Aquatic Habitat Guidelines Program has created Marine Shoreline Design Guidelines as comprehensive guide of shoreline assessment and management techniques. This guide provides detailed methods for site assessments, implementation of the nature-based solutions outlined above, and considerations and techniques for removal of coastal armouring.

You can take your project a step further and enroll your project with Green Shores and go through Green Shores® accreditation process. Find out more from the SCBC website (Green Shores for Homes and Green Shores for Shoreline Development) and this Green Shores for Homes Credits and Ratings Guide.

Photo credits: Jake Dingwall, Kelly Loch, Maria Catanzaro, Weaverling Spit Restoration 'before' photos courtesy of Todd Woodard, Samish Nation Natural Resources, after photos by Maria Catanzaro